From «Popular Mechanic», January 1949

|

| Is this the last of the great propeller-driven passenger liners? That's what . some predict as the twin-deck giant takes its position on the timetables |

NEWEST and biggest of the de luxe air-liners — the Boeing Stratocruiser that costs 1½ million dollars a copy-goes into regular service this year.

The great 114-passenger double-deckers will cut solid hours from existing schedules. New timetables will read: "New York to London, 11½ hours instead of 14½ hours," and "San Francisco to Honolulu, 8½ hours instead of 12 hours."

Not only is the Stratocruiser the latest conventional airliner, it probably is the last of them. Most engineers agree that the next big passenger planes will be powered by gas turbines and will be either jet propelled or will use the turbines to turn conventional propellers. The Stratocruiser, they think, is the last of the big passenger-carrying planes that will use reciprocating engines.

| Lined up in front of a Boeing Stratocruiser is part of the 30 tons it carries into the air. It will accommodate 114 passengers on daytime runs or 27 in "Pullman" berths and 39 in chairs when used as combination sleeper-and-day plane |  |

Since the plane represents the end of an era from the design standpoint (not from the point of view of the flying public, because the big ships will be the best available for years to come), let's compare it with one of the first planes ever built for airline service. Twenty years ago a popular airliner was the tri-motored all-metal Ford, whose three engines produced a total of 660 horsepower. Any one of the Stratocruiser's four engines develops more than five times as much.

|

| Berths are seven inches wider than those in standard rail sleeper cars |

The Ford carried 12 passengers in a compartment that measured 350 cubic feet. The same number of passengers can sit, with room to spare, in the big Boeing's cocktail lounge alone. The baggage and express compartments of the new plane are twice the volume of the Ford's passenger compartment.

The Ford cruised at 95 miles per hour, two miles an hour slower than the Stratocruiser's landing speed. The Ford's fuel tanks held 235 gallons of gasoline. The Stratocruiser carries 32 times as much fuel and its drinking-water tanks alone are equal to one third the total fuel capacity of the Ford. The Stratocruiser can fly 4200 miles nonstop, a distance that would require seven intermediate landings for fuel by the earlier airliner.

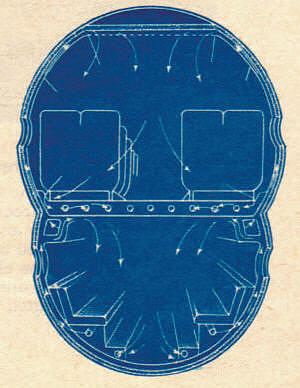

A passenger on the Ford was deafened by noise, subjected to cold drafts and made uncomfortable by changes in altitude. Stratocruiser passengers never need to raise their voices and they breathe a manufactured atmosphere adjusted to a pleasant summer temperature and humidity. The cabin retains sea-level pressure up to 15,000 feet and is reduced to an apparent altitude of 6000 feet at the 25,000-foot ceiling.

|

|

| Spiral stairs, left, join two decks of the giant air carrier. For large families or groups of friends there are spacious staterooms, above, that are made up with divans or couches |

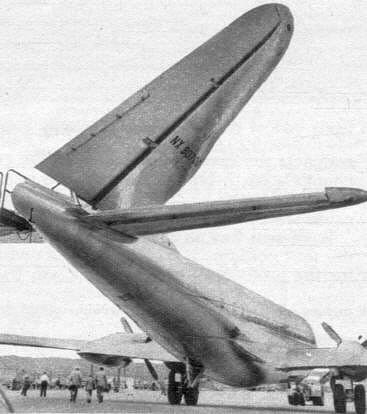

Briefly, the Stratocruiser has a span of 141 feet, is 110 feet long and has a tail that stands 3$ feet high. Four Pratt & Whitney Wasp Majors, each with 28 cylinders, individually develop 3500 horsepower for take-off. The loaded plane has a take-off weight of 71 tons and cruises at 340 miles per hour at air levels of up to 25,000 feet. One reached a speed of 498 miles an hour in a dive.

A fleet of 55 Stratocruiser is under construction in Seattle for Pan American World Airways, American Overseas Airlines, United Air Lines, Northwest Airlines, British Overseas Airways and others. When all deliveries are made, it will be possible for a passenger to fly around the world in less than 70 hours by transferring from one Stratocruiser to another.

|

| Looking toward rear of main passenger cabin on the upper deck of the 340-mile-an-hour luxury airliner |

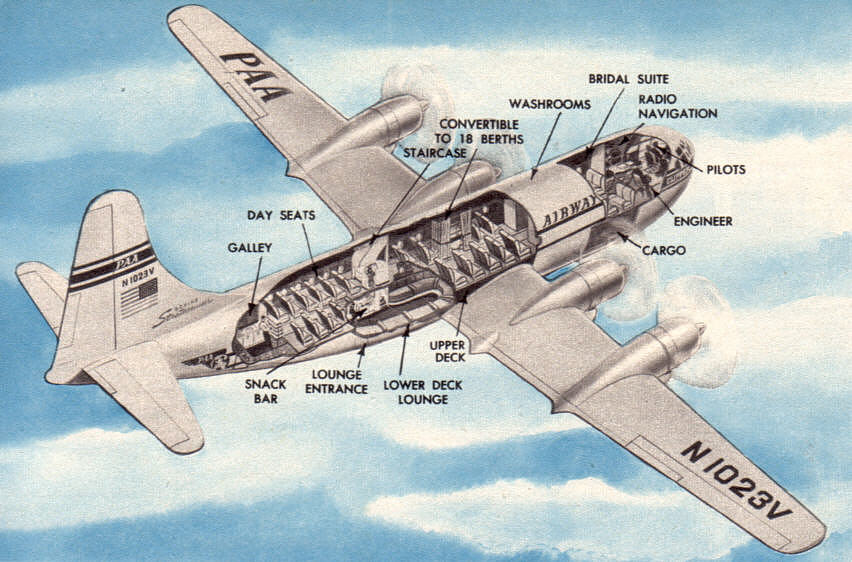

As a day plane, the big carrier seats up to 114 passengers; as a combination day-and-sleeper plane it carries 25 chair passengers and 27 "Pullman" passengers on the upper deck plus 14 chair passengers in the lower-deck lounge. A spiral stairway connects the two decks. A stewardess can change a berth-type seat into a bed in one minute. Upper berths fold out from the cabin walls.

Each seat has an armrest "control panel" that contains a call bell and a switch for the prefocused reading light, ash tray, an "occupied" sign, seat number, reclining-back adjustment and a receptacle into which may be fitted the dining-tray leg.

| Upper and lower berths are curtained off for complete privacy. Right, food is loaded through special door | |

|

|

|

| Cutaway view showing how Pan American World Airways will use two-deck space of the $1,500,000 transport |

The plane has an extra-large galley with its own side hatch so that food and supplies may be loaded or unloaded from the galley without being hauled through the passenger compartment. Commodious dressing rooms for men and women are provided. The crew, which may number up to eight, has its own toilet facilities in the control compartment.

Interior decoration was given considerable attention because a passenger's surroundings can contribute to travel sickness and fatigue or actually reduce them, depending on the colors and patterns used. Clashing colors and "busy" designs were ruled out. The basic color system employs dark colors at floor and seat level with light "high value" colors on the walls and ceiling. This treatment adds to the illusion of spaciousness and prevents eye fatigue when shifting the gaze from inside the plane to the outside. This is important because the Stratocruisers will normally fly above the clouds in constant sunshine during daytime hours.

|

|

| Hinged tail, right, allows big Boeing ship clearance getting through hangar doors. Upright, the rudder tip is 38 feet high. Above, large metal containers at left in galley hold fruit juices and hot soups |

Stratocruisers destined for different routes are given individualistic cabin color schemes. Planes for the bleak North Pacific run to the Orient are being finished inside with rough-textured fabrics of beige and reddish-brown to help create a feeling of comfortable warmth. Aircraft on the Honolulu run will have tropical interiors featuring bamboo trim. Conservative oak

Flexwood paneling goes into ships ordered by British Overseas Airways. After testing several color mock-ups, however, it was decided that all control compartments will be the same. They will be finished in medium gray and dark maroon, with black non reflective paint for instrument panels.

|

| Fourteen passengers can be seated comfortably in the air-conditioned lounge, situated on the lower deck |

The control compartment has so little resemblance to the cramped cockpits of older transports that pilots are calling it the "pilot's parlor." Normal crew consists of pilot, copilot, flight engineer, radio operator and navigator. Each has a comfortable, roomy chair. Among other innovations are the paneled windows that give exceptional visibility.

The seven windows at eye level are of a new non icing type and consist of two layers of plate glass separated by a plastic core and by a transparent three-molecule-thick layer of electrically conductive material. Electricity flowing through this layer keeps the window at a frost-and-ice-free temperature. Hot air prevents icing of the other windows.

Even severe icing conditions are no handicap at all to the plane. Leading edges are kept warm by hot air from eight combustion heaters flowing through special wing and tail passages. Even when it is 20 degrees below zero outside it is possible to keep all leading edges at 80 degrees above zero. The four-bladed reverse-pitch electric propellers are protected from ice by resistance heating elements running lengthwise in each blade.

With the exception of the hydraulic rudder-control system, the Stratocruiser is virtually an electric airplane. Its six 28volt d.c. generators create enough power to serve the domestic needs of a 114-home community.

There are 119 motors and 411 lights on the plane, 482 switches and 10 miles of wiring. Power demands range from the 616 amperes required for raising or lowering the landing gear to 1/100 ampere for burning a tiny compass light located in the control compartment. Two alternators and five inverters are used to supply current of the types needed, including 110-volt a.c. for electric shavers.

| Cross-section view of a Stratocruiser showing paths of air flow inside two decks. At 15,000 foot altitude, the passenger cabins still maintain their pressure at sea level |  |

The multitude of lights on the plane includes a 50-watt spotlight in the nose-wheel well to facilitate ground servicing, 36-inch fluorescent tubes for indirect lighting in the lounge, and "red and white" lighting in the control compartment. White lighting illuminates the instruments and controls at sunset to provide strong visibility and the white light gradually changes to red as the sky grows dark. The red illumination prevents night blindness and at the same time allows good vision. With the approach of dawn the red lighting gives way again to white.

The unique hydraulic rudder-control system is designed to provide pilot "feel" without undue effort. Two engine-driven pumps plus an accumulator in the tail provide enough power to move the huge rudder 20 degrees a second with no noticeable lag. If the hydraulic system should fail, a spring-tab control system automatically is available to allow manual operation.

Partly because of its size and complexity the Stratocruiser is believed to have been tested more thoroughly than has any other aircraft. Tests actually began in 1944 when the plane's military prototype, the C-97 Stratofreighter, was first flown. This cargo plane can carry as much as 20 tons of freight and has a ramp that permits the loading of four regular field ambulances into the fuselage.

Both cargo and passenger versions of the design use a new wing that is 16 percent stronger, 26 percent more efficient, and 650 pounds lighter than the wing of the B-29. This improvement comes in part from the use of the new 75-ST alloy of zinc, magnesium, copper and aluminum for the skin and some extrusions. Spot welding is used extensively.

Flight tests of the Stratocruiser itself resulted in two tall filing cabinets full of test reports, two miles of 16-mm movie film and two miles of instrument tape. For parts of its flight test the first plane carried three tons of precision test instruments. It is estimated that the 700 hours of flying time involved in the tests cost nearly three million dollars. The test flights were equal to eight trips around the world at the equator.

Twenty years ago an airplane like the Stratocruiser hadn't even been dreamed of by serious engineers. The strides that air transport has made in two short decades makes one wonder what. flying will be like in 1969, just 20 short years from now.