From «Boeing Magazine», August 1950

To see how the Stratocruisers are doing along the world's airlanes, take a 30,000-mile jaunt with Test Pilot Lamson.

By ROBERT LAMSON A Boeing Test Pilot, Stratocruiser Project

At the English Channel, the fog reached up and smothered us. Somewhere beneath us lay the water; just behind us the green and brown patchwork of the continent, the sundrenched field we'd left at Frankfurt. Now we might as well have been flying inside a bowl of chowder.

We were bound for London, aboard one of American Overseas Airlines' Boeing Stratocruisers. It was an ordinary, run-of-the-sky Stratocruiser flight. That's why Don Kelley and I, from Boeing's flight-test department, were along; it was our job to see how the Stratocruisers were doing in their operations for five airlines.

We'd known about the fog before we hit it, of course. The plane's first officer had got the word from London flight control: the London area was thoroughly socked in, with visibility at three-quarters of a mile. As I looked out at the white stuff rolling along the windows of the control cabin, I couldn't help thinking: just a few years ago any airline pilot would have been quick to ask permission to go to an alternate landing field. But not today, not with the Stratocruiser and the all-weather instruments at the pilot's command. Today it was routine stuff. About the only comment was Capt. Bob Borgeson's. He looked at me and grinned. "Lamson, you'll get to see the new Calvert approach lighting system at the London Airport."

When our radio navigation showed we were approaching the southeast shore of England, we received radio instructions to descend to 3,000 feet for the initial approach into the London control area. Immediately the signal was given to start descent.

Ray McCuen, the flight engineer, throttled the engines back to a point where they were almost idle. The first officer called London approach control, reporting our position and requesting approval for an instrument landing on the London-Airport approach.

Approval came through as we passed over the "Z" marker, which gave us a visual and audio cheek of position over the London radio-range station. Captain Borgeson started a gentle turn to the starboard and soon I could hear the low-frequency intermittent signal coming from the outer marker of the ILS range. As we droned down the approach glide path, with the soup swirling about us, there was no more concern in the cockpit than if we had been making a dear daylight landing. I found myself wishing the passengers could be up there with us, observing the obvious confidence these crewmen had in themselves, in the approach-equipment on the ground, and in their airplane. In these few months of airline operation, the Stratocruiser had become a proven, accepted craft.

When we were down to an altitude of 300 feet, I could make out the highdensity Calvert lights marking the runway approach. At 200 feet the lights furnished us such dear guidance that for a moment I forgot we were navigating a typical London fog. Power was slowly throttled back and the airplane settled smoothly onto the runway. Without missing a beat, the first officer was calling out the after-landing check-list items. The big plane coasted along smoothly and, with only a light brake application, we taxied off the runway at the mid-intersection point. So aptly controlled had the fog-bound landing been, both as to position and speed, that the touchdown had allowed the full length of the runway for deceleration. Not that it was needed, though; nor were reverse pitch and heavy braking. As we taxied up to the ramp, I heard London tower calling another aircraft somewhere up there in the soup: "Clear to land, runway 1-2. Visibility one-half mile, ceiling . . ." I looked down the flight apron and could barely see the second hangar beyond the ad building.

|

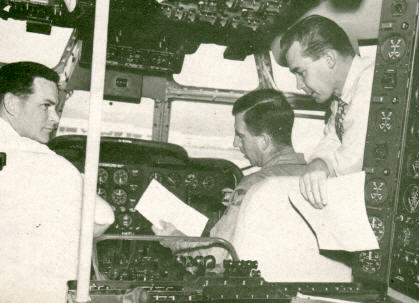

LEFT -Author Bob Lamson [center] trained airline men on Stratocruiser. Here he's instructing AOA crewmen. BELOW - FAA 'Cruiser at John Rodgers field, Hawaii. |

|

Then, looking back in the cockpit, I watched the flight crew go through the shutdown procedure in the same methodical way they had teamed together throughout the entire flight. No rush, no tension, no confusion. It was just another routine flight, another day's work for a crew that had swiftly accepted the newest airliner in America.

That was the way Kelley and I found it, everywhere we went aboard the Stratocruisers. Routine flights, every one, aboard an aircraft that took new accomplishments in its stride, day after day. That's the basic fact of the report Don and I brought back to Boeing: The Stratocruiser has been accepted, by crews and passengers, as the world's foremost airliner, and in record time.

Altogether, during some two months, Don and I traveled 30,000 routine miles in our "sampling" of the Stratocruiser in airline operation. We were surprised to find how many other people were traveling by Stratocruiser, too.

During early spring, only two months after the last Stratocruiser delivery, the Boeings already were carrying about 4000 passengers across the Atlantic every month, matching the number carried by all surface liners on this route. Some 3000 were flying Stratocruiser between the West Coast and Hawaii. Today, with summer sending vacationers abroad, the numbers have increased-to the point, in fact, where Pan American World Airways has had to double its Stratocruiser service across the Atlantic.

To handle so many passengers, an airliner obviously must obtain good utilization. Utilization good enough to fit into this category is not often obtained during the first year of operation, yet operators have been achieving close to seven hours' utilization per day with the Stratocruiser. This means an average of seven hours, day in and day out, including layups for maintenance.

Some observers feel that, because the Stratocruiser is what they term a "natural," it may be giving up to nine hours per-day service before the year is out. Later, as maintenance crews become more familiar with the airplane, even higher utilization with high passenger and freight-load factors can be expected. A few operational analysts will not agree entirely with this, but they will agree that the Stratocruiser has a pilot and passenger appeal that has exceeded expectations. They'll agree, too, that it has exceeded expectations in the way of handling characteristics, cockpit visibility and flight-crew confidence - a fact we didn't know until we learned it first hand from the personnel of five airlines.

Already these qualities have enabled two operators to obtain CAA approval of Stratocruiser landings under conditions that have in the past been considered below minimum. These operators are licensed now to land under cloudceiling minimums of 200 feet and atmospheric visibility of one-half mile.

These low-weather minimums never before have been granted an airplane so recently off the production line. As a pilot, I can speak for many when I say this is a real accomplishment. The London landing was only the first of two under these conditions which Don and I witnessed on our tour. On neither was there any apprehension on the part of the flight crew, nor any stretching of sensible safety margins.

This low-weather-landing approval demonstrates conclusively, so far as I am concerned, that safety and size go hand in hand. Airplane control and maneuvering rate, too, are no monopoly of the small plane; they're a matter of design rather than size. If there were any combat necessity for the Boeing B-29, B-50 or B-47 bombers to do acrobatics in flight, they could surprise you. It is a fact, as many Air Force people could tell you, that one of these planes has been barrel-rolled in flight on more than one occasion.

Another example of control accomplishment is on display daily between New York and London with the overocean flight technique employed by AOA. This operator is flying its Stratocruisers manually over the North Atlantic, without autopilot — a procedure that never could be applied on long flights in today's (or any day's) small aircraft. In case you might expect the pilots to be complaining about this system, let's bring back AOA's Captain Borgeson for a moment. It's somewhere in the early morning, with the Atlantic lost in the inkwell below us. Bob's been at the controls for three hours, without relief. He's reclining back in the seat, his feet resting on the support bar, two fingers lightly adjusting the main control wheel.

He'd been sitting there silently for a long time when he suddenly turned to me. He jiggled the control wheel with a finger. "Lamson," he said, "she flies like a bird."

Such ease of control gives a tremendous boost to the confidence of the airplane's flight crews. It makes for precision during instrument flying, during landing and takeoff, and undoubtedly it cuts down fatigue. And, in the final, important computation, it all adds up to increased safety in flight.

Please don't get the idea that I'm trying to give Boeing exclusive credit for this accomplishment. After all, there are the vendor manufacturers who designed and supplied navigation aids, radio and traffic-control improvements, and component parts. And the airline operators, too-Northwest, Pan American, United, British Overseas and AOA-each had an active hand in the final development of the Stratocruiser. Not to mention the fact that it's the operators who are doing the operating.

Nonetheless, the Stratocruiser is a Boeing; basically, its capabilities are possible because of the long line of other, earlier Boeings ahead of it. That means a lot to a man like me because I just about grew up in the Boeing tradition. It means quite a bit to some others who helped mold that tradition, back in the pioneering twenties, too: men like "Rube" Wagner, Ralph Johnson and Harry Huking. Then they were flying Boeing 40B-4s into and out of such places as North Platte, Nebraska; Rock Springs, Wyoming, and Elko, Nevada. Today they're flying Boeing Stratocruisers for United Air Lines, on the San Francisco-Honolulu run.

I remember the night Don and I drove out to Honolulu Airport to greet a UAL Mainliner Stratocruiser arriving from the Coast. Rube Wagner was at the controls, and we cornered him in the pilots' room shortly after he landed. I asked the obvious question: "How do you like the Stratocruiser, Rube?" Rube grinned and gave me an answer that, for my money, covers the situation completely.

"She's another Boeing," he said.